Amid efforts to expand coronavirus testing, laboratory operators and state health officials are navigating a thicket of supply shortages, widespread test backlogs, unexpected snafus and unreliable results, often with no referee—prolonging the national crisis.

Public health experts say fast, widespread testing is a key requirement for safely reopening businesses and returning to something close to normal life, because it would allow officials to detect new cases quickly and stem outbreaks.

As President Trump and many of his advisers focus more attention on the nation’s economic reopening, lower ranking officials are trying to sort out the testing puzzle and individual labs are vying for supplies in a fractured and exhausted marketplace.

“It is a little bit insane. Everyone is running around trying to get as much as they can from every vendor,” said David Grenache, the lab director at TriCore Reference Laboratories in Albuquerque, N.M. “Laboratories are competing with each other to get needed resources,” he said, and often coming up short.

The private sector hasn’t so far been able to deliver nearly enough tests to meet the huge demand in the U.S., more than six weeks after the Food and Drug Administration allowed private companies to manufacture test kits and put them to use without having to be approved.

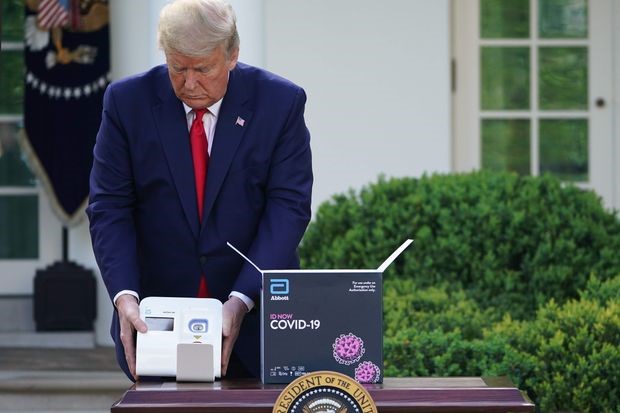

A signal White House effort to ramp up testing showcases the obstacles. Federal officials sought to distribute a new device by Abbott Laboratories around the country, but the push fell short when supplies proved scarce and the device’s reliability faced doubts, according to state officials and laboratory experts.

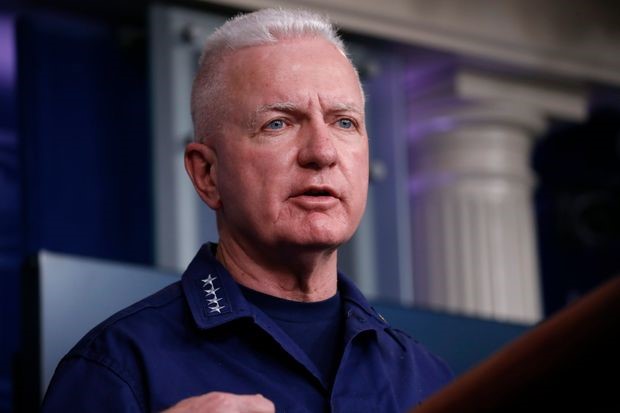

By one top administration official’s account, testing through April will only meet about half the capacity that is needed. Adm. Brett Giroir, the administration’s testing coordinator, said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal on Thursday that he believed three or four million tests would be performed in April.

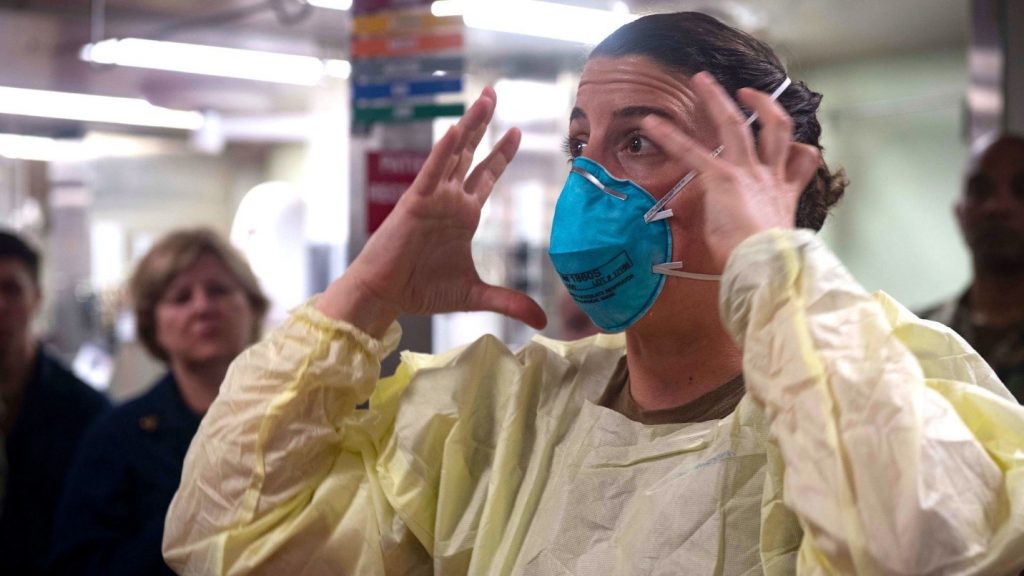

With medical workers facing shortages and the CDC recommending the voluntary use of face coverings, many are wondering when they can get access to N95 masks. WSJ’s Gerald F. Seib explains. Photo: SARA ESHLEMAN/GETTY IMAGES

But he set a specific target for needed testing capacity at six million to seven million tests a month, while projecting the U.S. would reach that goal in May. Dr. Giroir said that estimate was based on an assumption that there would be 300,000 new cases of the virus a month, even as pockets of the nation are expected to reopen.

The next day, Dr. Giroir gave a rosier projection at a White House briefing, saying only 4.5 million tests would be needed based on an estimated 200,000 new cases a month. In an interview Saturday, he explained the change: “I revised that down from the podium.”

Some in the federal government, including Mr. Trump and his top advisers, say the job of figuring out how to further expand testing belongs to states and private labs. Mr. Trump tweeted Friday: “The States have to step up their TESTING!”

Dr. Giroir said Saturday the federal government was still fully engaged in fixing testing. “Believe me, because we’re working 18 to 20 hours a day, the feds are not relinquishing our system to the states,” he said.

On March 30, Mr. Trump had touted in a Rose Garden news conference the new testing device by Abbott. He said then, “We have built an incredible system.”

President Trump showed a coronavirus testing device from Abbott Laboratories on March 30.

PHOTO: MANDEL NGAN/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

Mr. Trump said the Abbott tests could deliver “lightning-fast results in as little as five minutes,” at a time when politicians around the country were fretting over long backlogs at conventional laboratories. The federal government bought hundreds of the devices to distribute to states.

That marquee effort soon ran into the supply-chain issues that have plagued the testing buildup. State officials found they couldn’t easily obtain enough of Abbott’s single-use cartridges to actually test patients, they said. Each cartridge contains the chemicals and other components needed for the machine to process one test.

As of last week, Abbott said it had distributed about 600,000 cartridges for the machines.

“We understand there is great demand from both the public and private sectors for our rapid point-of-care test,” said Scott Stoffel, Abbott’s spokesman. “We’ve been clear from the outset on what we could initially provide, and we’ve met every commitment.”

In recent days, state and hospital officials found in internal studies that the devices frequently produced inaccurate results, leading at least one hospital to return the devices, they said in interviews.

Mr. Stoffel said the company believes the inaccurate results are rare, and said it has made changes to its instructions for using the machines to address them.

The obstacles in the push for national coordination of the lab supply chain follow an earlier failure when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention botched its first tests for Covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. A faulty component forced the CDC to recall the tests.

Almost a month later, the FDA cleared labs to devise tests of their own. Most of the dozens produced since identify the genetic footprint of the virus, but use different machines, methods and materials, including obscure ones such as chemicals derived from bacteria found in hot springs and deep-sea thermal vents.

Most require a long list of components that come from different producers, including swabs, throwaway polystyrene parts, chemical reagents, glass pipettes, pipette tips and more, resulting in a complex supply chain that easily breaks down when there is a shortage of any particular element.

The process is also used to detect other respiratory viruses. A huge surge in U.S. demand for the components during the pandemic stressed that system. Promega Corp., a Madison, Wis.,-based testing-chemical maker, told the Journal orders for their products had increased 10-fold so far this year, compared to the same time last year.

Absent a clearly organized system for allocating materials across the industry, “it feels a little bit like natural selection, doesn’t it?” said Andy Last, the chief operating officer at Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., a California-based laboratory equipment manufacturer.

The government has stepped in at times, and rebuffed calls for aid at others.

Adm. Brett Giroir, the administration’s testing coordinator, this month.

PHOTO: ALEX BRANDON/ASSOCIATED PRESS

“There is zero probability we can help on plates,” said Dr. Giroir, the testing coordinator, referring to the disposable plastic trays used in the testing process, in an email this month to a doctor who had inquired about supplies on behalf of a commercial laboratory with dwindling stores.

“This was one lab in one place that is having trouble getting plates,” Dr. Giroir said to the Journal, adding that it would have been inappropriate for the federal government to intervene.

He said the administration had made strides by speaking to “every manufacturer” of key testing chemicals. “There are some spot shortages around,” he acknowledged.

In Sunday’s briefing, Mr. Trump said the administration was preparing to use the Defense Production Act, which can compel manufacturers to make needed products in an emergency, to direct one U.S. facility to produce 20 million additional swabs per month but played down concerns about shortages. Of the chemicals used in testing, he said: “We’re in great shape. It’s so easy to get.”

Dr. Giroir, days earlier, told the Journal that the supply shortages don’t rise to the level that the government should use powers such as the Defense Production Act. He also said some important lab suppliers, like testing-chemical maker Qiagen NV, a Dutch biotech with a key factory in Germany, are primarily overseas.

“I can invade Germany if I want to get Qiagen,” Dr. Giroir said. “But I can’t do anything aside from that.”

Lab directors, including in America’s hardest-hit areas, say the supply chain problems are severe. When an order of a testing chemical never arrived last week, “we delayed some testing as a result of it,” said Dwayne Breining, the laboratory director at Northwell Health, a New York City-area health system.

“In Seattle, no one seems to have enough supplies to do the amount of testing that is in demand,” said Geoffrey Baird, a laboratory director at the University of Washington’s health system.

With normal market forces warping under the pressure, some labs stockpiling goods and others struggling to get them, many see a clearer role for the federal government to resolve the mismatch.

“Even libertarians want the government to combat deadly, contagious diseases” when it can actually help, said Michael Cannon, a health policy analyst at the Cato Institute, which advocates for a small federal government that keeps its hands out of nearly every corner of American life.

Senior federal leaders, including Mr. Trump, have waffled over their role in ramping up testing. One official said the government’s job was to “rapidly prototype something,” before states and companies take over. Anthony Fauci, the longtime National Institutes of Health official, de-emphasized testing Friday, after weeks of arguing it is the key to reopening the economy, saying what “we’ve been hearing is essentially ‘testing is everything,’ and it isn’t.”

Mr. Trump backed away from a March 6 promise that “anybody that wants a test can get a test” to say, a month later, tests were unnecessary for people in much of the country.

Vice President Mike Pence said Sunday on NBC’s “Meet the Press” that “there is a sufficient capacity of testing across the country today for any state in America to go to a Phase 1 level” of reopening, with some business activity and daily life resuming.

An administration official said in an interview last week that widespread testing will be primarily important after the country starts reopening, rather than beforehand. Independent health experts dispute that.

“We can’t let anyone go back to work until we’re confident that the case numbers have stabilized. There’s no way to do that effectively without testing,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University.

So far, the U.S. has tested about 3.7 million people, about 1% of the population, according to data gathered by Johns Hopkins University researchers. In South Korea, which experts praised for a nimble response to the pandemic, about 560,000 people have been tested, also around 1% of the population, according to that country’s disease prevention agency. But testing ramped up far more quickly there, allowing officials to better contain the country’s outbreak.

Separate tests, for antibodies that would show a person had recovered from an infection, are also in development, but their usefulness in catching cases before the virus spreads isn’t clear.

Some U.S. labs continued to face significant backlogs. An internal Quest Diagnostics Inc. report this month viewed by The Wall Street Journal showed all of the company’s laboratories had backlogs of at least three days to perform tests, and in some cases as many as five days.

Drive-through testing at a Quest Diagnostics parking lot in Tampa in March.

PHOTO: MARTHA ASENCIO RHINE/TAMPA BAY TIMES/ZUMA PRESS

Quest spokeswoman Wendy Bost said Thursday the company is now able to turn around tests sooner, in as little as one day for priority patients and two days for most others. She said the company can do 45,000 tests a day. Quest had earlier attributed the backlog to huge initial demand.

A regional microbiology lab that serves a network of seven St. Louis-area hospitals has the capacity to run about 1,000 tests a day, said Scott Isbell, a professor at Saint Louis University and lab director at the university-affiliated hospital that belongs to the network. But a shortage of swabs used to collect test specimens means the lab still has to ration tests.

“I have 300 swabs in my lab right now, and that’s got to last me until I get my next supply, and I don’t even know when that will be,” Dr. Isbell, a clinical chemist, said in a recent interview. “We aren’t really able to test the spouse of a nurse who worries they might have been exposed.”

An invoice viewed by the Journal shows another laboratory ordered about $13,000 worth of swabs on March 13. As of April 15, the supplier, Medline Industries Inc., estimated it could fill the order on May 18.

Dr. Giroir said the U.S. government was on track to purchase and distribute 12 million swabs by the end of May, including more than five million in the next few weeks.

Lab operators and their advisers say they are trying to crack the codes of who gets what and when on their own.

“It is more deli-style on swabs. When your number comes up, you are served,” said Greg Knapp, an executive at Vizient Inc., which advises hospitals on purchasing supplies.

When swabs aren’t the bottleneck, other supply-chain problems can throttle testing. Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City could theoretically do about 3,000 tests a day. “We’ve never approached that because of other shortages,” said Sterling Bennett, a lab director there, adding that in practice the lab can typically do somewhere between 10% and 30% of that volume.

Roche Holding AG, one of Dr. Bennett’s suppliers of the chemicals used in tests, said “the supply situation may be challenging in the short term” and that it was prioritizing customers most able to perform tests, such as those that already have its machines set up.

Promega, the Wisconsin chemical maker, said it is prioritizing orders as they come in, and filling them to the extent possible.

As of Friday, Dr. Bennett said he had received a good stock of testing chemicals, but had learned his main swab supplier was down to a two-week supply.

Some federal health officials recognized the risks of gaps in the supply chain early, but lacked the authority to take action. Starting in early March after hearing alarms from labs, FDA officials began an impromptu effort to track lab supplies.

“We have proactively reached out to over 1,000 manufacturing facilities, because people weren’t compelled to provide us information,” said Jeff Shuren, the FDA’s top official overseeing medical devices and tests.

FDA officials said they have also worked with labs to come up with stopgap alternatives when shortages emerge, publishing suggestions on a website. But, Dr. Shuren said, “We have neither the authority nor the ability to determine where tests or supplies should be distributed.”

Mr. Trump and officials discussed the coronavirus pandemic response at Federal Emergency Management Agency headquarters in March.

PHOTO: EVAN VUCCI/PRESS POOL

At the White House, responsibility for the nationwide testing problems hopscotched from official to official in February and March. In late February, Mr. Pence took over the federal response from Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar.

On March 11, the president asked Jared Kushner, his son-in-law and adviser, to help coordinate with the private sector on testing and other elements of the federal response, administration officials said. The next day, Mr. Azar tapped Dr. Giroir as the new testing coordinator.

Almost immediately after the FDA cleared the Abbott device, called the ID Now, it became a symbol of the administration’s pandemic response. After a request from a White House official, an Abbott worker walked an ID Now over from one of the company’s Washington offices, and it became a prop at the March 30 news conference, people familiar with the matter said.

One of the people said the White House asked for the device so it could test officials.

Around the same time, Dr. Giroir said, he ordered the government to buy hundreds of the devices to distribute to states—which got 15 each—and federal agencies. He said he envisioned the tests being used, for instance, at nursing homes and on Indian reservations.

Abbott shares rose after its testing devicewas touted in a White House newsconference.Stock and index performanceSource: FactSetAs of May 1, 5:22 p.m. ET

%News conferenceAbbott LaboratoriesS&P 500 IndexJan. ’20Feb.MarchApril-40-30-20-1001020

“I was not going to be a part of a biological genocide of the Native American population,” he said.

But the hype the administration created around the ID Now grew far beyond those niches. On Friday, Mr. Trump called the Abbott device “the hot one” during a daily virus briefing.

When state officials received the machines in early April, challenges quickly emerged. For one thing, the machine can do one result quickly, in under 15 minutes according to the company, but was never meant to run the large volumes of tests needed during a pandemic. Other machines, including one by Abbott, can run 96 samples at a time over several hours, far outpacing the ID Now in the course of an afternoon.

Also, state officials quickly found their initial allotment of cartridges—single-use containers for all the test ingredients—was sufficient only to verify the machines were working, and not actually test patients. For weeks some states were unable to obtain more from the government’s online lab supply store.

Officials in Oklahoma, for instance, were told another 800 tests had been set aside for them on April 9, according to Elizabeth Pollard, the state’s deputy secretary of science and innovation. But she said they had received no guidance on when they would get them. “It is a little bit of a black box for us,” she said. None had arrived as of Sunday morning, a spokeswoman said.

Dr. Giroir said he only bought about a quarter of the cartridges Abbott initially produced because he didn’t want to siphon off the supply available to private customers in hard-hit places.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How should testing for coronavirus be ramped up? Join the conversation below.

“I did not want to rob New Jersey and New York and other places for Montana,” he said. He said he had added thousands of cartridges to the stores available to states last week.

Other administration officials said they had learned from Abbott in recent days that the speed at which the company can make the cartridges is the limiting factor. The White House has tried to strike “the right balance between guidance and not disrupting the natural balance if the federal government weren’t going to intervene,” one said.

Last week, some state officials and lab workers at hospital systems said they are seeing ID Nows produce dubious test results.

At the University of Maryland Medical System, scientists compared the Abbott device to their traditional testing system and found the ID Now was wrong about 7.5% of the time when testing samples positive for coronavirus.

“The only thing that would have been acceptable was 100%” accuracy, said lab director Robert Christenson.

Coronavirus testing devices developed by Abbott Laboratories at a mobile clinic in San Francisco on Thursday.

PHOTO: JOHN G. MABANGLO/EPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

Lab directors at two other hospitals said in interviews they were seeing inaccurate results on positive samples as much as 25% of the time.

Abbott officials concluded the problem was caused by a liquid used to preserve samples, the lab directors said, that could cause the specimens to become too diluted.

On Wednesday, the FDA said Abbott would be changing its label to preclude use of the preservative. Abbott’s Mr. Stoffel said when samples aren’t stored in the liquid, “the test is performing as expected.”

Dr. Christenson, a clinical chemist, said he planned to use the devices in hospital labs, not at patient bedsides, and needed to store samples to transport them. State officials worried the device’s limitations could reduce the machines’ usefulness in settings like drive-through testing sites where large numbers of samples are collected.

Dr. Christenson said he asked Abbott to take back the devices, which the health system had purchased directly. Abbott accepted the return collegially, he said.

“In our practice, it wasn’t going to work,” he said.