When will life return to normal? This is the answer of epidemiologists, as embroidered by one of them, Melissa Sharp.

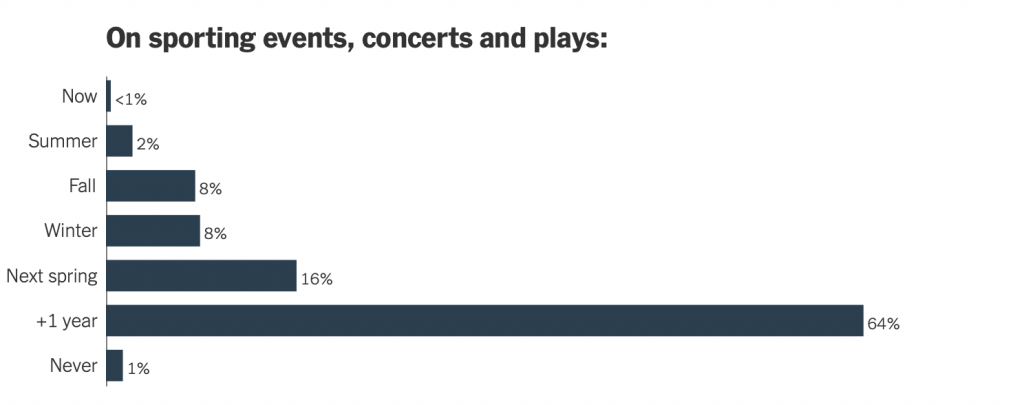

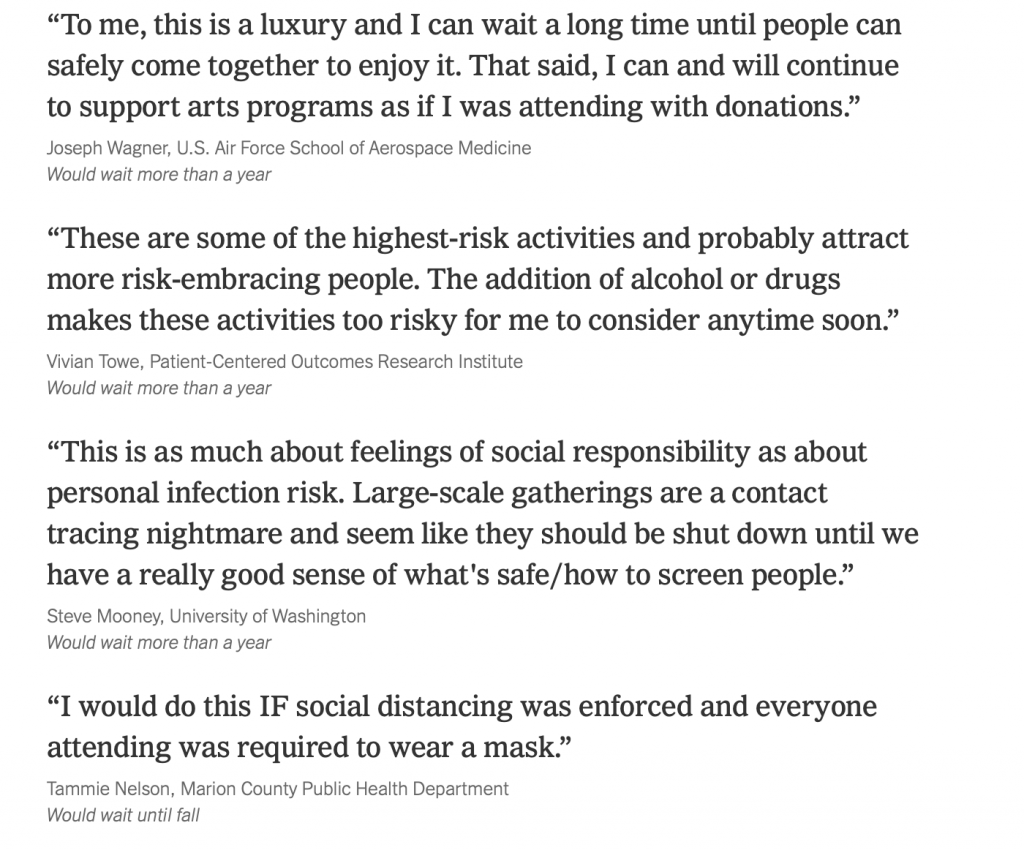

Many epidemiologists are already comfortable going to the doctor, socializing with small groups outside or bringing in mail, despite the coronavirus. But unless there’s an effective vaccine or treatment first, it will be more than a year before many say they will be willing to go to concerts, sporting events or religious services. And some may never greet people with hugs or handshakes again.

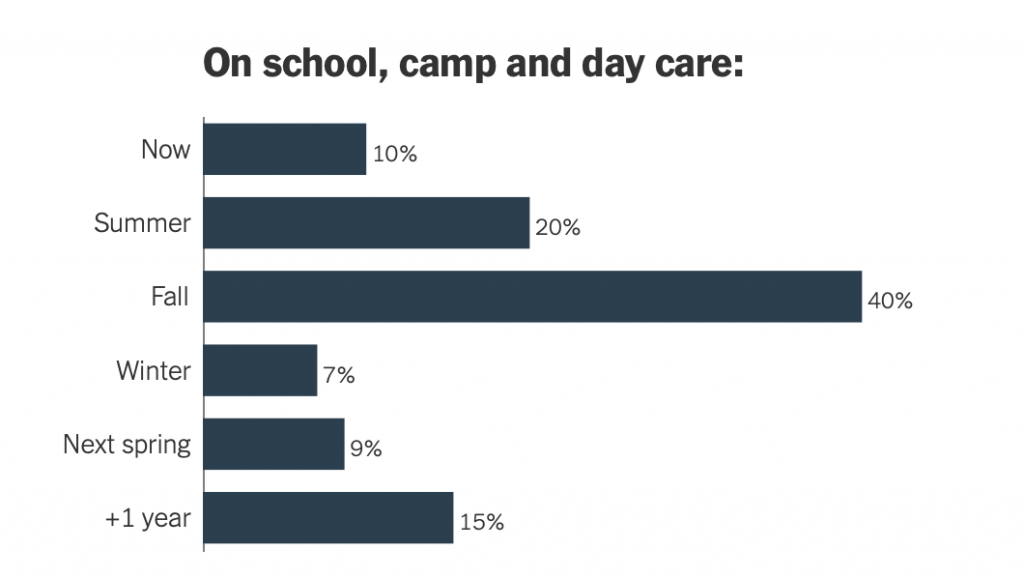

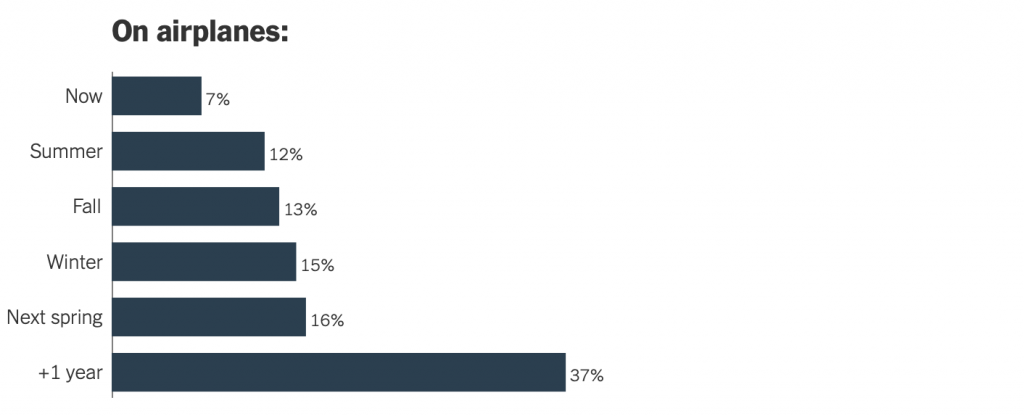

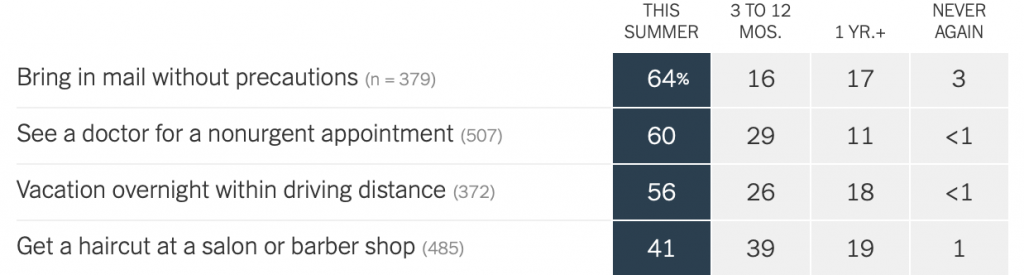

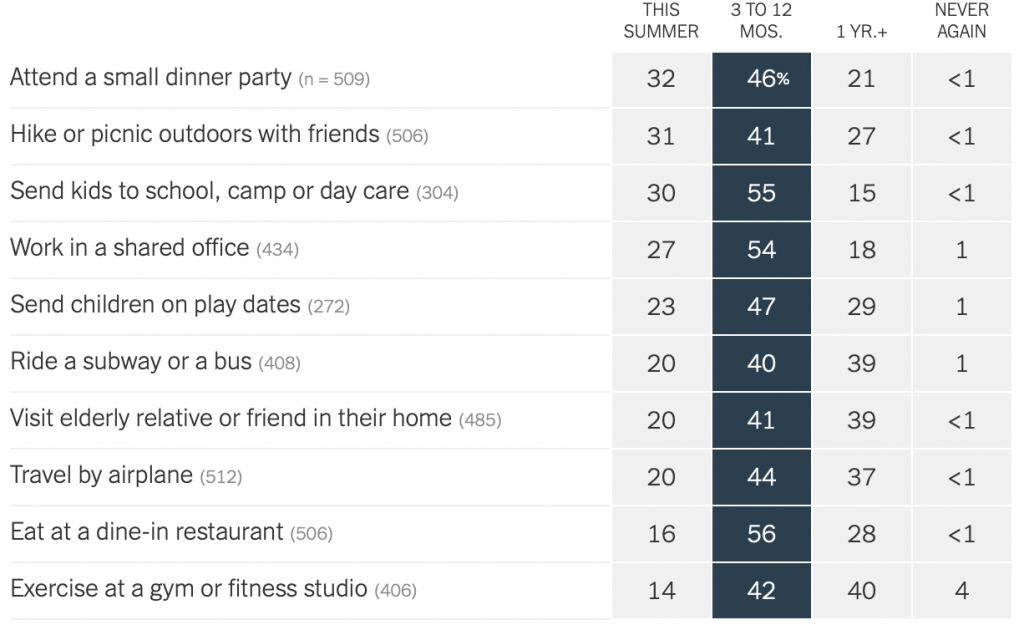

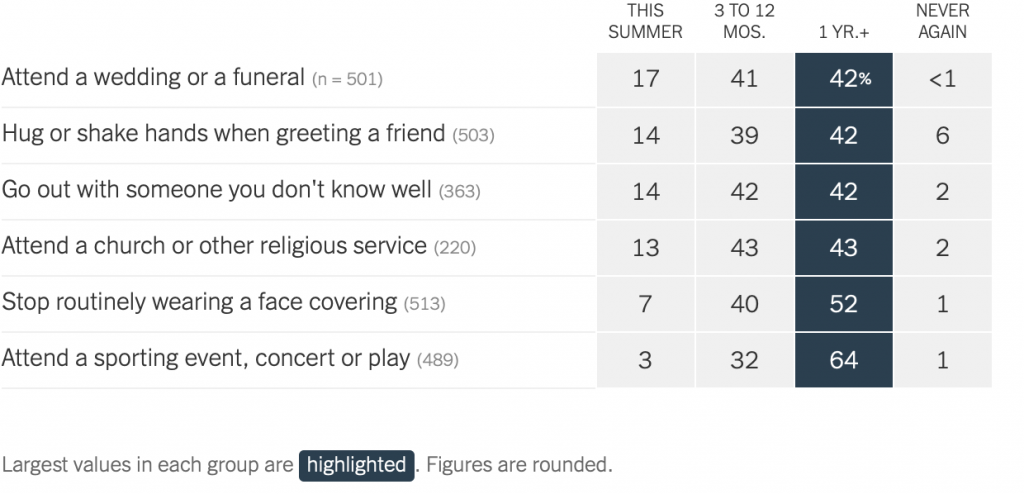

When epidemiologists said they expect to do these activities in their personal lives, assuming the pandemic and response unfold as they expect

Activities they said they might start doing soon

Later in the next year

Maybe a year or more

These are the personal opinions of a group of 511 epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists who were asked by The New York Times when they expect to resume 20 activities of daily life, assuming that the pandemic and the public health response to it unfold as they expect.

Their answers are not guidelines for the public, and incorporate respondents’ individual life circumstances, risk tolerance and expectations about when there will be widespread testing, contact tracing, treatment and vaccination for Covid-19. They said it’s these things that will determine their actions, because the virus sets the timeline. “The answers have nothing to do with calendar time,” said Kristi McClamroch of the University at Albany.

Still, as policymakers lift restrictions and protests break out nationwide over police brutality, epidemiologists must make their own decisions about what they will do, despite the uncertainty — just like everyone else. They are more likely, though, to be immersed in the data about Covid-19 and have training on the dynamics of infectious disease and how to think about risk.

They mostly agreed that outdoor activities and small groups were safer than being indoors or in a crowd, and that masks would be necessary for a long time.

“Fresh air, sun, socialization and a healthy activity will be just as important for my mental health as my physical well-being,” said Anala Gossai, a scientist at Flatiron Health, a health technology firm, who said she would socialize outdoors this summer.

Some said they would refrain from nearly all of the 20 activities until a vaccine for the virus had been widely distributed. Others said they would wait for a vaccine to do the indoor activities on the list.

“As much as I hate working at home, I think that working in a shared indoor space is the most dangerous thing we do,” said Sally Picciotto of the University of California, Berkeley, one of the 18 percent of respondents who said they expected to wait at least a year before returning to the office.

The responses were collected the last week of May, before the death of George Floyd in police custody spurred protests across the country. These mass gatherings are likely to cause a rise in cases, some epidemiologists said. “There’s a risk, and it’s hitting the communities hit hardest by the pandemic, and it’s heartbreaking,” said Andrew Rowland of the University of New Mexico.

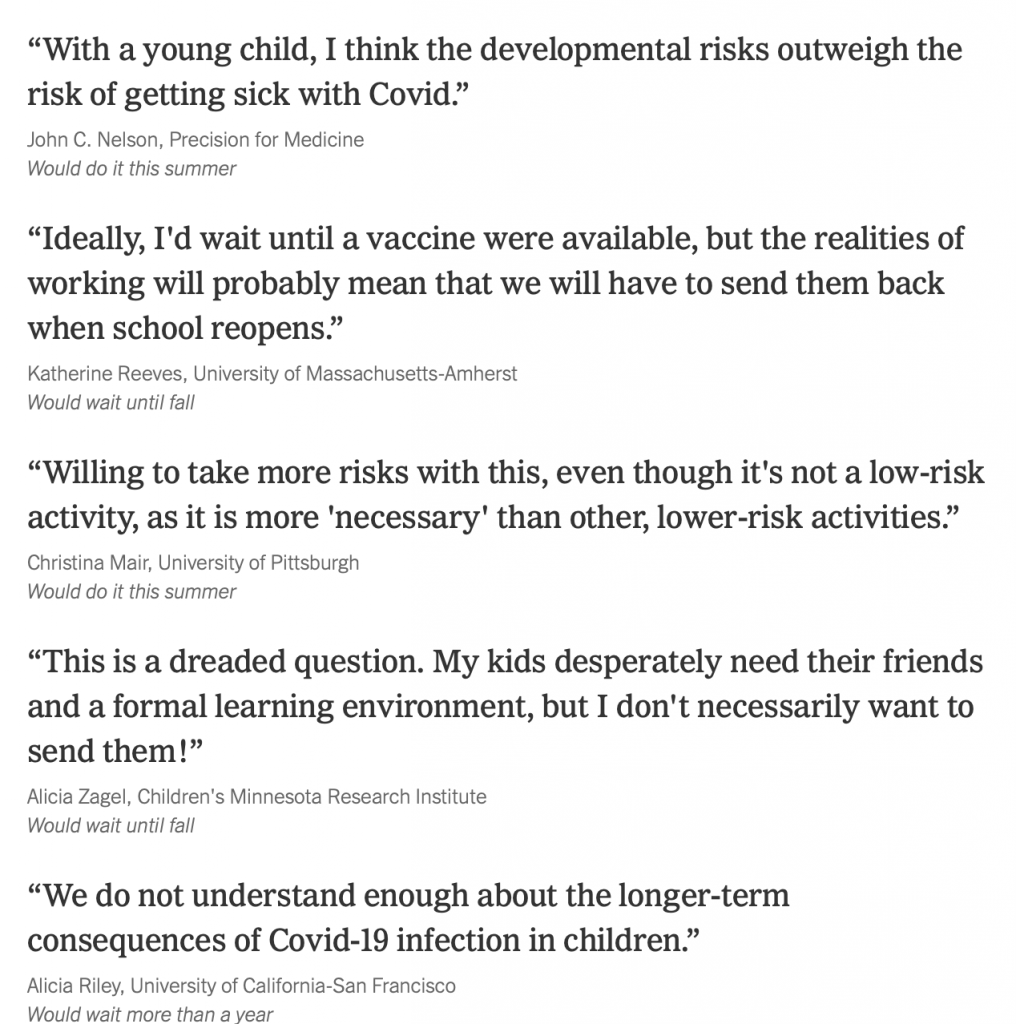

For some of the activities, there was significant disagreement.

Some said hair salons were relatively safe — they aren’t usually crowded and have hygiene requirements — while others said a haircut had a high risk because of the face-to-face contact. Forty-one percent would go now or this summer, but 19 percent plan to wait at least a year. One-third said they would attend a dinner party at a friend’s home this summer (many specified outdoors with appropriate distancing), while one-fifth said they would wait more than a year, potentially until there was a vaccine.

Epidemiologists say they are making decisions based on publicly available data for their region on things like infections and testing. Before choosing whether to do an activity, they might evaluate whether people are wearing masks, whether physical distancing is possible and whether there are alternative ways to do it. Because there is a chance of a second wave of infections, they say they may become less comfortable with certain activities over time, not more.

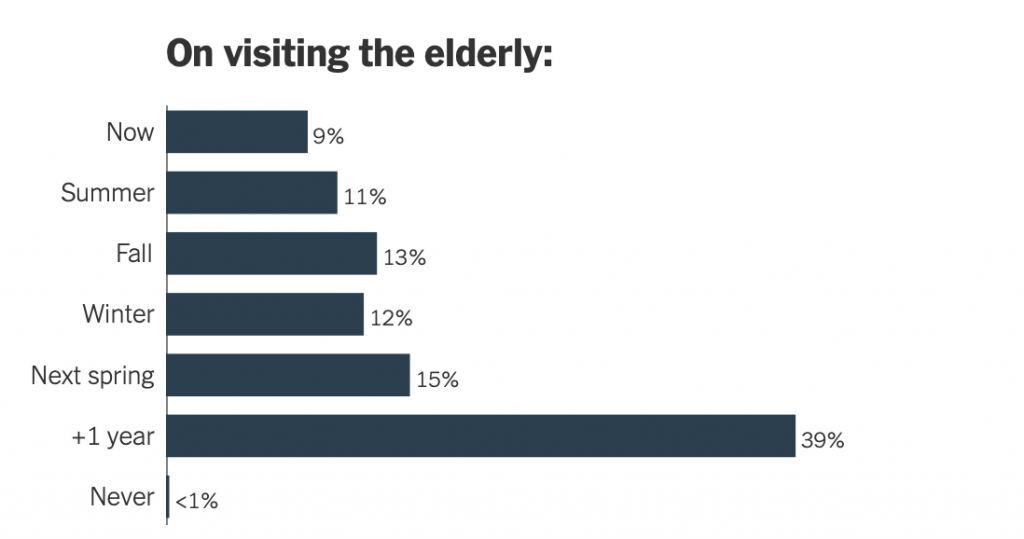

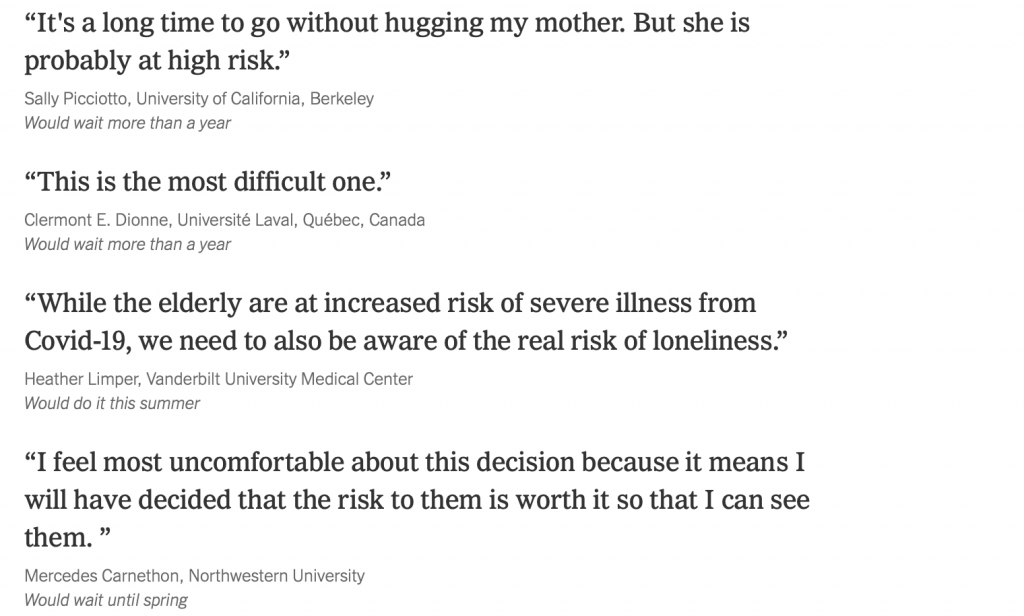

Like everyone, they are also weighing practical considerations. Those who are required to go to an office or hospital every day are doing so, even if they think it would be safer to remain home. The need for child or elder care forces difficult choices. Activities that seem optional, like attending a concert, are easier to avoid. More than 70 percent of respondents said they or someone in their household was at high risk of serious illness or death from the disease.

Melissa Sharp, who recently received her doctorate, will soon fly to Europe to begin a fellowship. But for now, while she is staying in Florida with family, including high-risk relatives, she has been extraordinarily careful, “cocooning” and avoiding activities that she considers less risky than flying.

One of her quarantine hobbies, she said, has been epidemiology-inspired needlepoint: “It says, ‘Well, it depends,’ because that’s really our slogan.”

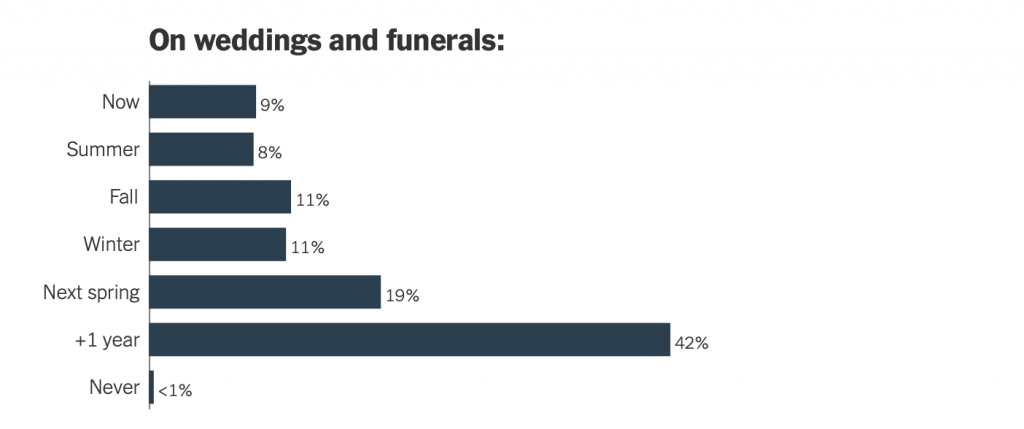

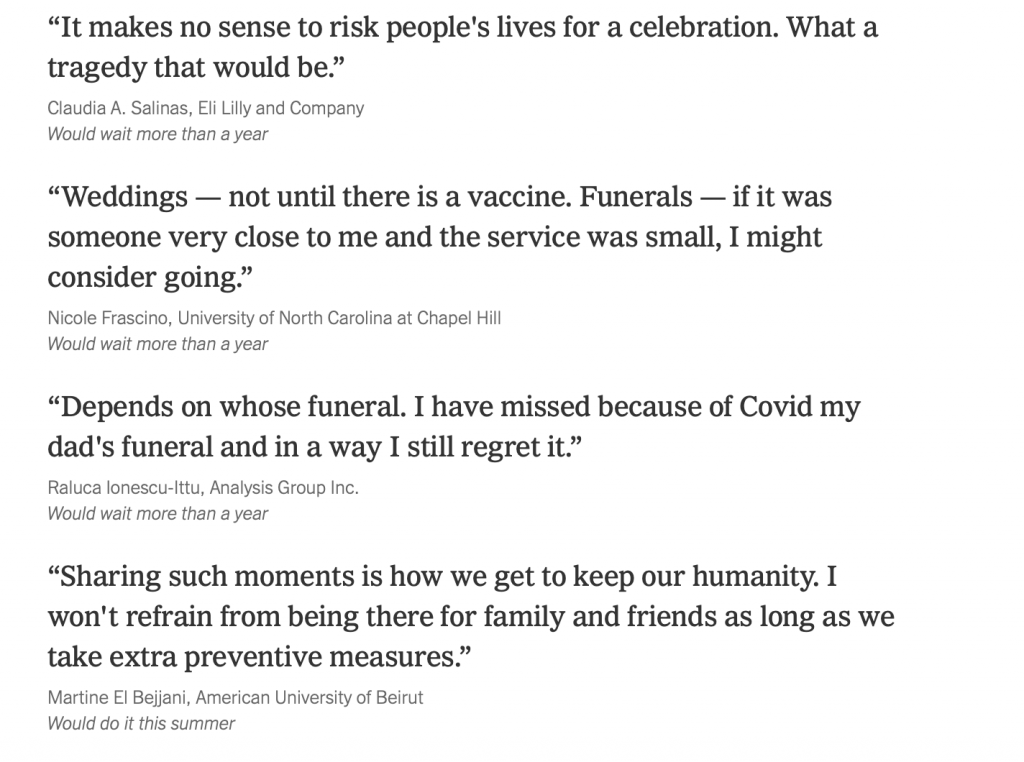

The scientists are weighing coronavirus risks against the benefits of certain activities, including emotional well-being. While both funerals and weddings carry risk by bringing together large groups of people, several said they would prioritize attending a funeral. Some are choosing to socialize or send children to camp because of benefits like mental health, education or household harmony.

Ms. Sharp said she’d consider dating after a period of confinement. “I’m young and single, and a gal can only last so long in the modern world,” she said.

For Robert A. Smith of the American Cancer Society, a haircut might be worth the risk: “It really is a trade-off between risky behavior and seeing yourself in the mirror with a mullet.”

Sometimes, their professional expertise and personal lives are colliding. Ayaz Hyder, of Ohio State University, said he was advising his mosque on how to reopen and to conduct Friday prayers. “Balancing between public health practices and religious obligations has been very eye-opening and humbling for me as an academic,” he said.

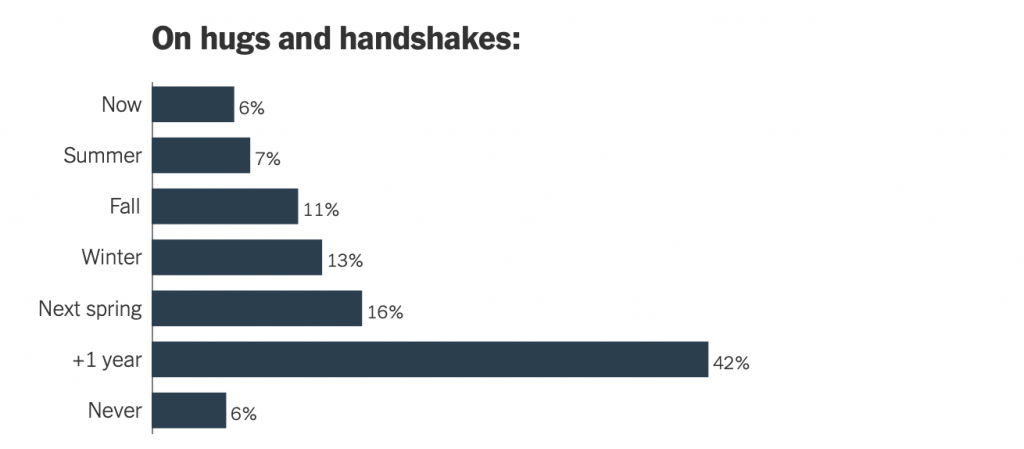

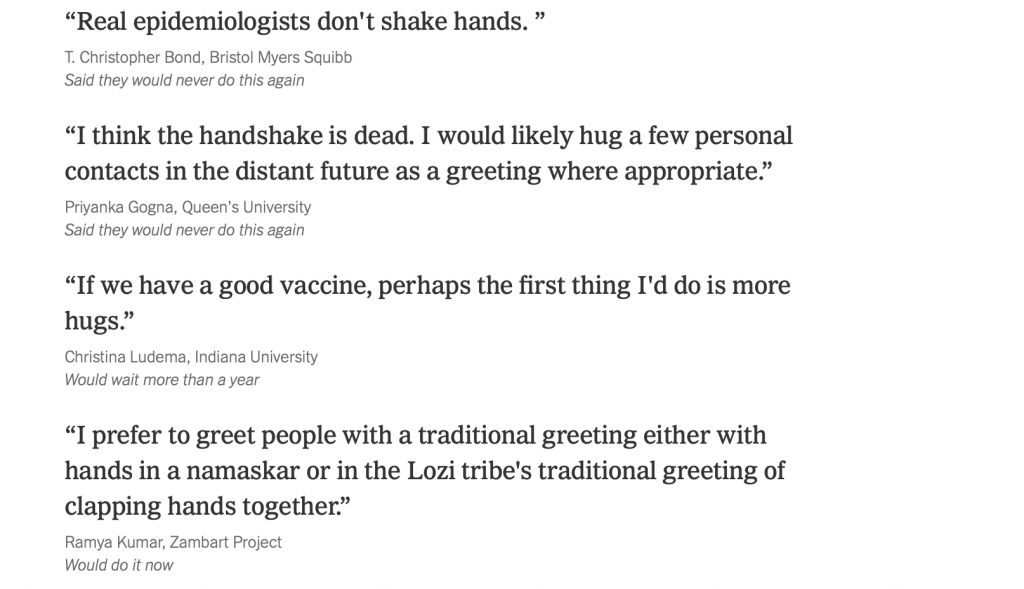

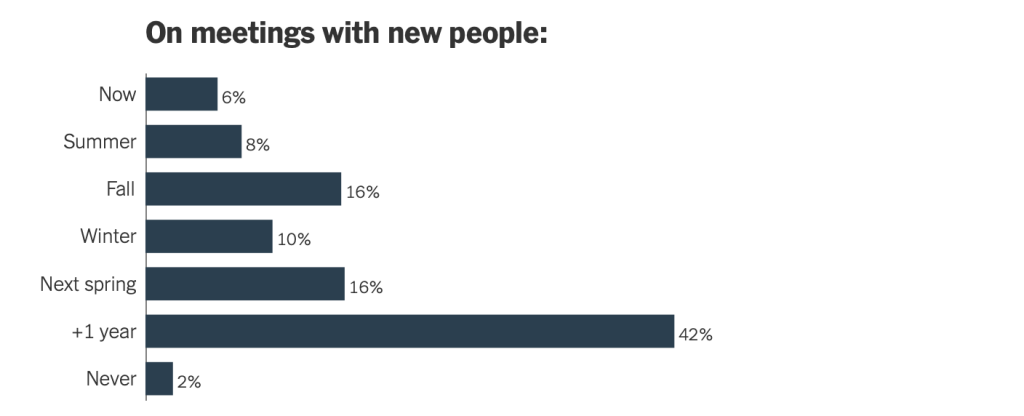

Many epidemiologists said they may never greet people the same way again. Forty-two percent of the sample said they would not hug or shake hands for more than a year, and 6 percent said they would never do either again.

“The worst casualty of the epidemic,” said Eduardo Franco of McGill University in Montreal, is the “loss of human contact.”

Others lamented it less: “Always hated those particular needless exchanges of pathogens and unwanted touching,” said Carl V. Phillips, who runs Epiphi Consulting.

About 6,000 epidemiologists were invited to participate in the survey, which was circulated to the membership of the Society for Epidemiologic Research and to individual scientists. Some said they were uncomfortable making predictions based on time because they didn’t want to guess the timing of certain treatments or infection data. “Our concern is that your multiple choice options are based only on calendar time,” 301 epidemiologists wrote in a letter. “This limits our ability to provide our expert opinions about when we will feel safe enough to stop social distancing ourselves.”

More than three-quarters of the panel said their daily work was connected with the Covid-19 pandemic in some way. Nearly three-quarters work in academia, 10 percent work in government, and the remainder work for nonprofit groups, private companies or as health care providers.

Surveys of ordinary Americans show that many people without epidemiology training also think it will be months or longer before many common activities can become routine again. A recent survey from Morning Consult found that more than a quarter of Americans would not visit a shopping mall for more than six months, and around a third would not go to a gym, movie or concert.

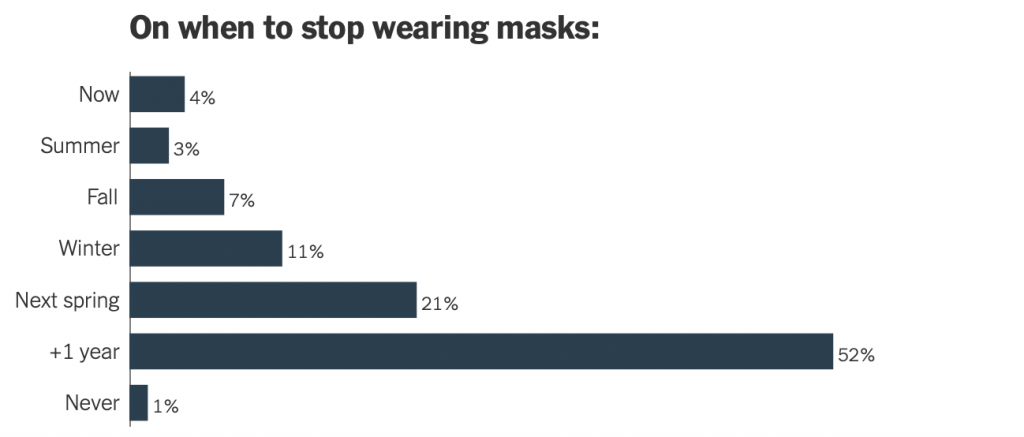

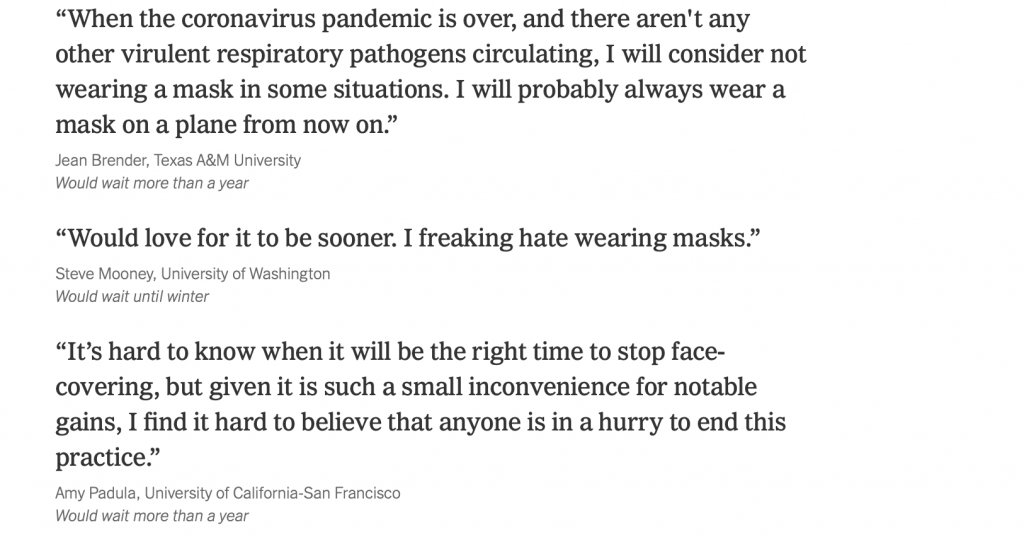

One thing the epidemiologists seemed to agree on was that even when they return to normal activities, they will do them differently for a long time, like socializing with friends outside or attending worship services online. A majority said it would be more than a year before they stopped routinely wearing a mask outside their homes.

People often ask when things will return to normal, said T. Christopher Bond, an associate director at Bristol Myers Squibb. “At first I told them: ‘The world has changed and will be different for a long time. This is the crisis of our lifetime and we need to embrace it,’” he said. “But that depressed them. So now I say, ‘Well, we know more every day.’”

Additional comments from epidemiologists on life and social distancing